Vietnam: growing old before growing rich

Vietnam is a rapidly-aging society that's still in the early innings of its economic development. This poses unique challenges, and opportunities, for one of the world's fastest-growing economies.

TL;DR

The popular notion of Vietnam as a “young country” is largely erroneous. The Vietnamese population is aging rapidly as birth rates decline and life expectancy increases.

Vietnam faces a unique challenge of growing old before growing rich. Vietnam will reach a ~3:1 worker-to-retiree ratio at ~1/2 the income of other countries with similarly old populations. This relatively low level of income will constrain Vietnam’s ability to support their elderly population and maintain its export-oriented economy.

Healthcare, elder care, financial services, and other retirement-related sectors remain underinvested and highly fragmented. These stand to benefit from Vietnam’s aging population.

Intro

To be honest, I didn’t plan on writing a second installment on my thoughts about Vietnam. My last post on the topic was a collection of observations that I attempted to contextualize using a brief overview of Vietnam’s recent economic history and current political climate, with some prognostication thrown in for good measure.

That was before I came across a piece from the World Bank regarding aging in Vietnam and into the rabbit hole I fell. For all its developmental success over the last ~40 years, Vietnam faces a severe and under-appreciated aging problem. Vietnam’s median age of 32 is relatively young by global (but not Southeast Asian) standards, but it belies a fundamental problem for the country’s prospects: Vietnam is one of the most rapidly-aging economies on Earth and is doing so at relatively low levels of income.

If you haven’t yet read by first piece on Vietnam, please do so now. My hope is that the additional perspective provided below helps augment your understanding of Vietnam in terms of both its promise, its challenges, and opportunities for entrepreneurship and investment in Southeast Asia’s economic darling.

As always, I welcome constructive feedback, disagreement, or request for greater detail in the comments below. Furthermore, I am in great debt to the aforementioned World Bank piece that inspired my interest in Vietnam's age structure and from which, the material below borrows heavily. I strongly recommend anyone interested in learning more about Vietnam’s aging structure to read that report.

Everything’s relative: A primer on age structure

Before setting out to discuss Vietnam’s shifting demographic position, it is probably best to review some key demographic terminology that will come in handy later. The key thing to keep in mind is relativity. When discussing the effect of age structure on economic development, one must consider not just absolute, but also the relative sizes of age groups within a population.

Generally speaking, populations can be split into two primary groups: working age adults (typically defined as individuals aged 15-64) and non-working age adults (“dependents”). Because their needs and effects on current and future demography differ widely, economists typically further break down dependents into younger (age 0-14) and older (age 65+) groups. The total dependency ratio (TDR) is a key term indicating the ratio of the number of dependents to the population of working age adults in a given country. Economists use TDR and other metrics measuring the size of age groups relative to one another to help describe and project a society’s productivity and social needs. As TDR drops, for example, each dependent, young or old, is supported by a greater number of productive workers. Conversely, a rising TDR suggests each working age adult is responsible for a growing number of nonworking young and old individuals. Ceteris paribus, a falling TDR is a near-term tailwind to economic growth, governmental budgets, and rising living standards, while a rising TDR suggests the opposite.

Hanoi, we have a problem: Vietnam’s getting older

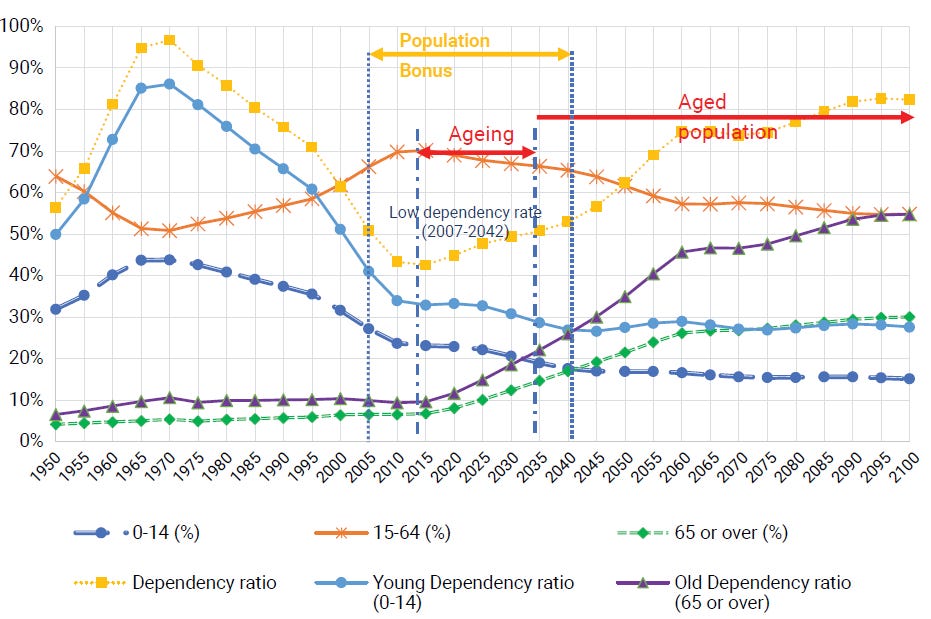

Using the concepts of productive adults, dependents, and TDR discussed above, we can start to understand the shifts afoot within the Vietnamese population. Below is a World Bank illustration of those concepts for Vietnam from 1950 until 2100e.

Figure 1: Vietnam: Demographic Projections, 1950-2100e

The boom times: 1975 - 2014

Vietnam’s 1970s TDR high water mark of ~100% (e.g. a 1:1 worker : dependent ratio) shown in figure 1 above was primarily youth-driven. High fertility rates and declining child mortality resulted in a high young dependency ratio (the portion of the total population below 15 years old) and correspondingly high TDR. It set the stage for the boom in labor supply that would help propel Vietnam’s economy though the 2010s.

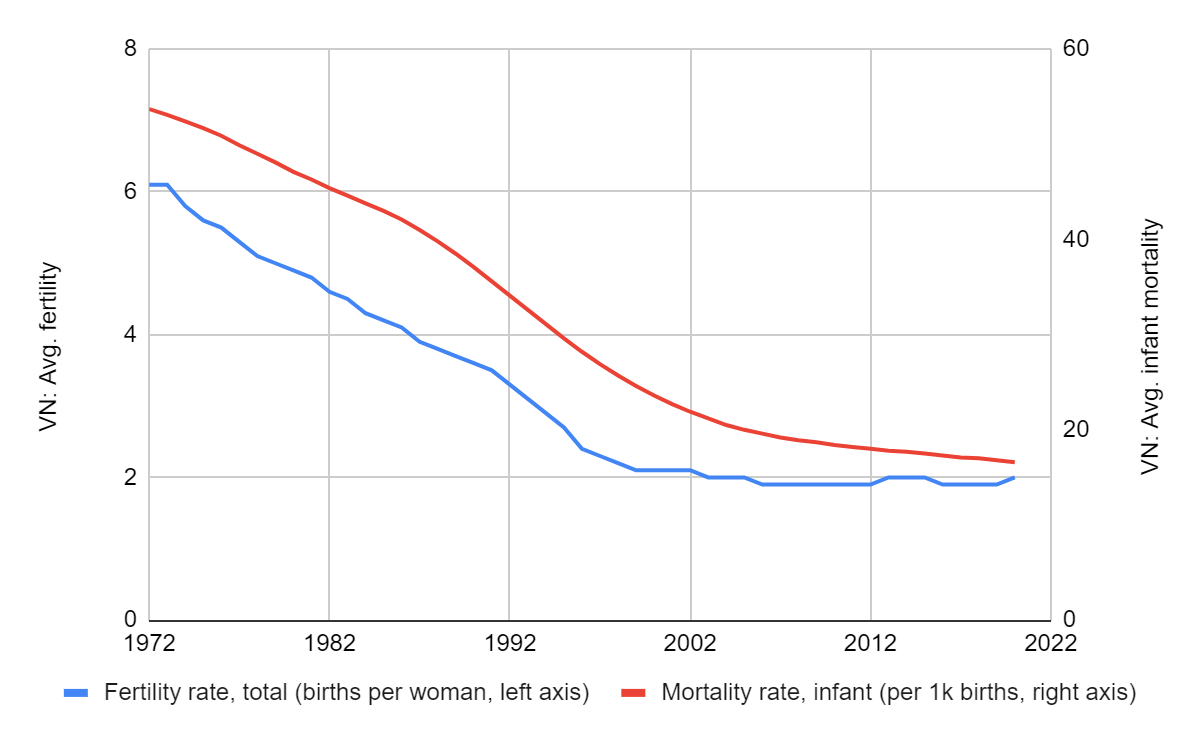

Starting in the mid 1970s, Vietnam’s sky-high TDR started falling rapidly, from ~100% in 1975 to ~43% in 2014 (figure 1). The primary reason for this shift was a dramatic decline in Vietnamese birth rates. Between 1975 and 2014, average children per woman fell from ~6 to ~2, approximating replacement levels (figure 2). The reasons for the decline in Vietnamese birth rates are many-fold and included significant increases in female education, access to family planning, and policies designed to slow population growth.

Figure 2: VN Fertility (left axis) and infant mortality (right axis), 1972 - 2020

While the relative shift in Vietnam’s age structure portended long-term challenges, it provided a short-term economic boom. This surge in labor supply coincided with the opening of the Vietnamese economy under Đổi Mới reforms in 1986, setting the stage for an economic windfall, as increases in labor supply and labor productivity increased per capita incomes 3x in real terms from 1986-2014, far outpacing the country’s middle income peers (figure 3).

Figure 3: VN GDP Per Capita, 1980 - 2022 (constant 2015 US$)

Growing old: 2014 - onward

Unfortunately, Vietnam’s labor pool post 1975 grew not just in absolute terms, but also in relative terms; it was transitory in nature.

By 2014, not only were fewer Vietnamese entering the workplace due to shrinking family sizes, adults were living munch longer into retirement than their predecessors. Live expectancy at birth, only 53 years in 1970, increased rapidly after the end of the Second Indochina (“Vietnam”) War to ~66 years in 1978 (a testament to war’s brutality), reaching an impressive 74 years by 2014 (figure 4). In 2014, those aged 65+ crossed 7% of the total population, the benchmark used by the World Bank to denote an “aging population.”

Figure 4: Vietnam life expectancy at birth, 1970-2020

Vietnam’s TDR has since grown from ~43% in 2014 to ~46% in 2021, primarily due to the continued aging of its society. Individuals age 65+ currently constitute ~9% of the Vietnamese population. World Bank estimates (figure 1) suggest that by 2040, Vietnam’s TDR and portion of those age 65+ will reach 50% and 20%, respectively. This represents a seismic change relative to current levels with significant implications for the country’s growth prospects.

What it all means for Vietnam’s economic future

Vietnam is not alone in being an aging society. The country’s 2021 old age dependency ratio (OAR, the ratio of those age 65+ to those age 15-64) of ~13% is decidedly middle-of-the-pack, ranking 102 of 217 countries measured, well behind the likes of Japan (51%), Finland (37%), Italy (37%), and a raft of other European much older (but much wealthier) nations.

The challenge for Vietnam is not only will it soon face the same challenges already borne by other aging economies, it will likely do so at a significantly lower level of income. Two ways of contextualizing Vietnam’s challenges are listed below. One approach is backward-looking with regards to the income levels at which peers hit Vietnam’s current OAR, while another is forward looking with regards to what levels of growth Vietnam will need to achieve to reach income parity with today’s similarly-aged societies.

Backward-looking: At what income level did other countries experiencing Vietnam’s current age structure

One way to contextualize Vietnam’s aging population relative to income is to consider at what level of income other countries encountered OAR levels comparable to those faced by Vietnam today.

Of the 40 other countries that passed 13% OAR between 1972 and 2021 and for which data is available, all but 3 of them did so at real GDP levels greater than Vietnam’s GDP today (figure 5). The median and mean GDP for these countries, in constant 2015 US$, was approximately $11,000 and $18,000 respectively, compared Vietnam’s 2021 2015 US$ GDP of $3,409.

Figure 5: Real per capita GDP (2015 US$) when each country crossed 13% OAR

Forward-looking: Economic growth needed for Vietnam to reach income parity with today’s similarly-aged economies

Another way to contextualize Vietnam’s aging population relative to income is to compare its projected OAR of ~30% and GDP in 2045 (figure 1) to the current income of countries that currently have similar OARs.

Current median and mean per capita GDP among the 36 countries with old dependency ratios currently between 25% and 35% is approximately US$30,000 and US$38,000 respectively. This means that Vietnam would need to achieve real GDP CAGR of ~9% to reach US$30,000 by 2045, nearly double the already-impressive real growth rate of ~5% it achieved since 1997 (figure 6 and figure 7). Even for an economy with a developmental track record as robust as Vietnam, this is a tall order. Put another way, Vietnamese workers will need to support their seniors with less than half the per-capita income of other countries that have a similar proportion of elderly citizens.

Figure 6: Old age dependency ratio vs. GDP

Figure 7: Number of countries with current old age ratio 25-35, sorted by 2021 GDP (current US$)

Policy implications

While this is by no means a policy-focused blog, some of the policy implications related to Vietnam’s aging population are too important to miss, so I’ll briefly parrot them here. Those seeking greater detail on policy implications for Vietnam’s aging populations should refer to materials from the World Bank and UN, among others, on this topic.

Vietnam is currently considered to be in a demographic window of opportunity, defined as having a TDR below 50%. This designation is meant to communicate a greater opportunity for a society to implement the structural shifts- social welfare and the like- needed to accommodate future increases in its elderly population. Currently, elderly Vietnamese report support from children as their primary way of paying daily expenses (32% of respondents), followed by income from work (29%), retirement benefits (16%), social assistance (9%), and other sources (14%). Figure 8 is from a UN report on elder care in Vietnam that breaks down Vietnamese elders’ support by age cohort.

Figure 8: Older persons’ income sources in Vietnam, 2011 and 2019.

To counteract its shrinking workforce, Vietnam will likely need to increase the quantity and productivity of labor by increasing its retirement age (currently age 60 for men and age 62 for women) and continuing its shift away from agriculture into higher value-add activities. Raising retirement ages may prove politically difficult in Vietnam, as reports suggest a preference for younger workers in manufacturing jobs. This means that middle-age and older workers who lose their manufacturing jobs may find difficulty in securing additional employment and making the required contributions to state-run pensions.

Additionally, Vietnam will likely need to increase access by the elderly to social welfare programs in order to counteract a shrinking workforces and growing share of retirees, particularly in light of signs that traditional familial support for the elderly, such as cohabitation, are on the decline. Increased spending, however, will need to be balanced such that government deficits do not raise interest rates to the determent of Vietnam’s export economy.

Business implications

While much ink has understandably been spilled regarding the public sector’s role in response to Vietnam’s aging demography, the country’s demographic shift poses opportunities for private sector entrepreneurship and investment.

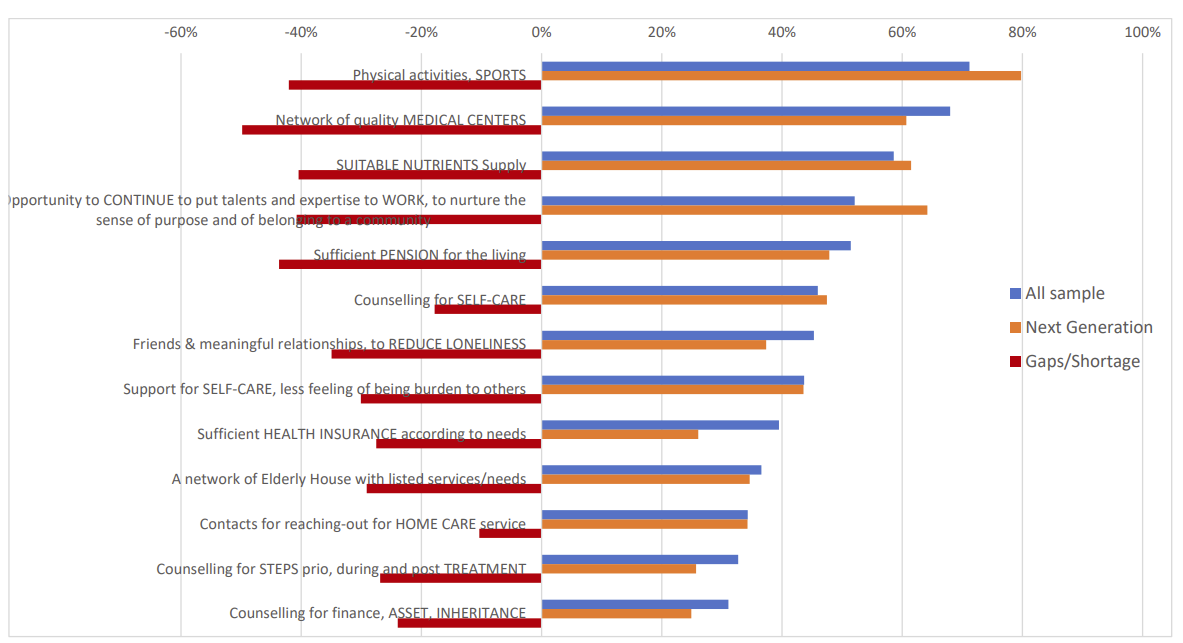

A 2021 UN report on the topic identified multiple promising sectors that stand to benefit from Vietnam’s aging population, including services most requested Vietnamese elders (figure 9).

Figure 9: Largest needs of current elderly, future elderly (“next generation”) and market gaps

Vietnam’s healthcare system has already attracted meaningful foreign investment, including a 2021 $200m investment by Singaporean sovereign wealth fund GIC. With the number of total hospital beds well below WHO recommendations and inadequate geriatric facilities nationwide, it’s likely that Vietnam’s healthcare sector will remain a recipient of additional private-sector investment. Vietnamese assisted living facilities remain highly limited, despite the aforementioned declines in intergenerational cohabitation and may too be an area of future growth.

Vietnamese elders report also report significant unmet economic needs, namely around securing continued employment into their elder years and in information related to retirement savings. Given Vietnam’s shrinking labor pool and relatively minimal levels of social welfare, helping seniors secure employment may be a win-win-win for entrepreneurs, employers, and the Vietnamese government.

A sincere thanks to Cheng Zishuang, Alwin Low, Max Robinson, and Huong Tran for their invaluable feedback.

Are you tired of me going on about Vietnam? Is there another SEA economic topic you’d like me to cover? Would you like to learn more about sectors likely to benefit from Vietnam’s aging society. Please let me know in the comments below. As always, thanks for reading!