Reflections on a visit to Vietnam

HCMC observations and what they could mean for the future of economic growth and political stability in Southeast Asia's fastest-growing economy

In February, 2023, I spent a week in Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC), Vietnam. It was my first time spending any appreciable time in Vietnam since 2013, when I interned with a HCMC-based Venture Capital firm. Below are some of my thoughts and observations regarding HCMC and its future, with some historical context thrown in for good measure.

As noted in my introduction, readers should interpret everything below as loosely-held hypotheses based on reputable statistics and / or personal experience whenever possible. I welcome constructive corrections, criticism, and suggestions for further exploration. With all that said, let’s get into it.

The past: Vietnam’s economic miracle

In 1986, the 6th National Congress of the Vietnamese Communist Party instituted the Đổi Mới (“renewal” or “innovation”) reforms that began opening the Vietnamese economy to private enterprise and foreign investment. Among the many reforms included in Đổi Mới were the overhaul of the legal frameworks pertaining to property rights, the establishment of corporations and LLCs, a redesigned tax policy with substantially reduced tariffs, the reduction of the government’s role in foreign trade.

These reforms are largely accepted to be the start of Vietnam’s “economic miracle” that dramatically improved Vietnamese living standards and transformed the landscape of Vietnam, including (parts of) its economic capital, Ho Chi Minh City. Foreign direct investment (FDI) accelerated rapidly, as did exports. In the nearly four decades since the Đổi Mới reforms, Vietnamese FDI was regularly the highest in ASEAN (ex Singapore) and export growth consistently outpaced overall economic growth.

The coincidence of Vietnam’s market reforms and the spillover effects of astounding Chinese economic growth allowed Vietnam to benefit immensely. Between 1986 and 2021, Vietnamese GDP per capita increased roughly 5x to US$3,400. When adjusted for purchasing power, Vietnamese incomes roughly equal those of their Indonesian neighbors.

The present: Observations of HCMC in 2023

Armed with some historical context regarding Vietnam’s recent history of economic development, I will now convey two key observations from my time spent there, including some potential root causes.

HCMC: A tale of two cities

I last lived in HCMC's central business zone (District 1) in 2013. I was shocked to find the neighborhood to still be unchanged in 2023, despite the rapidity of change that commonly occurs in Southeast Asia. Tân Sơn Nhất Airport’s welcome proximity to the rest of the city, the uninspiring parade of mid-height office buildings one passes from the airport into District 1, even many of the smaller shops I passed on the way into the city, were almost exactly as I remember then from a decade ago. Living in Jakarta and having recently visited Phnom Penh, I expected a HCMC that would be nearly unrecognizable from a decade ago. Instead, I easily retraced my daily walk into work, passing the New World Hotel and Bến Thành market, ending at the glimmering Bitexco Financial Tower. There were some changes, to be sure: a new mall and pedestrian area on Lê Lợi made the city feel more livable, and the perpetually almost-open entrances to HCMC’s first MRT line signified progress, despite the project being nearly a decade behind schedule.

Vietnam’s familiarity shocked me, given the country’s incredible economic progress in the intervening years. Since my last visit to HCMC in 2013, Vietnamese per capita income has grown by roughly 50% in real terms. By comparison, U.S. incomes grew roughly 13% during the same period, suggesting a crude HCMC : U.S. “time exchange rate” of ~1:4. Yet here I was, over thirty “U.S. years” later, easily navigating the city and eating at some of the same amazing bánh mì stalls I enjoyed in 2013. I was shocked by the city’s familiarity.

That sense of familiarity was shattered as soon as I walked down to the Saigon River and saw what lay on its opposite bank. Whereas D1 was oddly familiar, D2 was shocking in its newness. What had been an expanse of empty, low-lying empty grasslands in 2013 was almost completely replaced by a constellation of glass-enveloped office buildings, luxury condo developments, trendy yoga studios, and craft beer bars that are mainstays in any prosperous metropolis. Clearly, these were the artifacts of Vietnam’s economic success and the engine behind the city’s rapid urbanization.

The end result of HCMC’s “bolt-on” approach to development has resulted in a tale of two cities: anyone facing West sees the old and familiar, while those facing east see new, glimmering monuments to economic growth. It is a coincidence of geography that tempts extrapolation to the broader “West vs. East” geopolitical tug-of-war from which Vietnam has intermittently suffered and prospered.

An outward-looking population

Another notable observation from my time in Vietnam was a culture that seemed surprisingly open to the Western world. While my experience in Vietnam was by no means a random sample of the population, I encountered a degree of English fluency and interest in Western culture that far exceeded my experience living in Jakarta. Much of Vietnam’s relative openness could perhaps be explained by influence exerted upon it by its more powerful neighbors.

Foreign influence in Vietnam is nothing new, with the country having experienced nearly 2,000 years of Chinese, French, and Japanese rule, followed by significant United States involvement in the Second Indochina (aka “Vietnam”) war. That this parade of foreign powers lasted so long and ended less than 50 years ago perhaps goes a long way to explain Vietnam’s awareness of, and interest in, the world beyond its borders. With this in mind, perhaps it is no surprise that today’s HCMC is filled with Vietnamese people traversing streets with French names, while eating baguettes and wearing NBA jerseys, and yes, often speaking English.

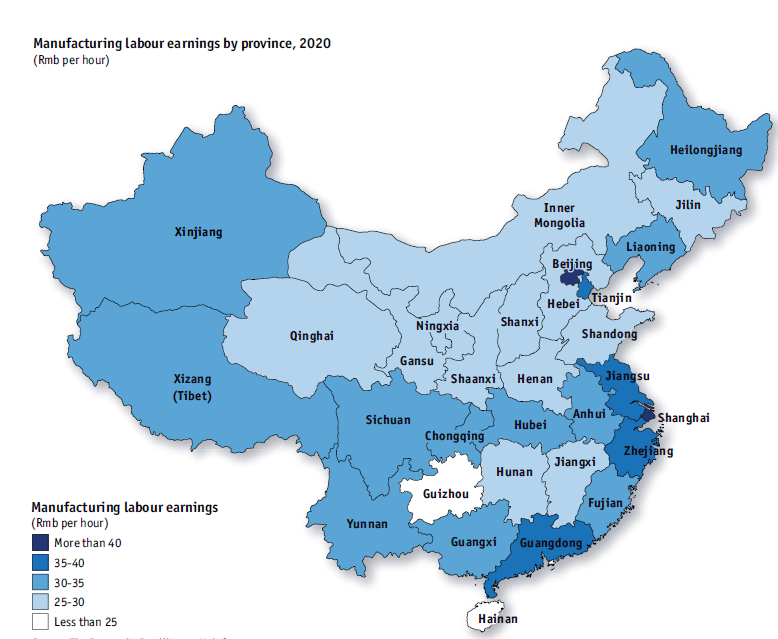

While Vietnam’s adjacency to larger regional powers has led to a difficult history of colonial rule, it has also been a major factor in the country’s recent economic growth. As neighboring China became the world’s factory in the 1980s and 1990s, its once-seemingly limitless supply of cheap labor started to become exhausted, with the cost of hourly labor from roughly US$0.60 per hour in 2002 to roughly $6.00 today. Furthermore, some of China’s most expensive manufacturing labor markets are in the country’s Southeast- near the Vietnam border.

By shifting manufacturing a relatively short distance across the border from Southeastern China to Northern Vietnam, manufacturers have reaped the twin benefits of significantly cheaper labor and sidestepping growing geological tensions between China and the United States, a phenomenon referred to as “friendshoring.” This, of course, has been to Vietnam’s benefit, further encouraging openness as a means to continued prosperity. This increase in Vietnamese manufacturing has proven to be one of the country’s primary engines of economic growth, increasing roughly 13x in real terms since 1984 and increasing to ~25% of GDP during that time.

A third reason for Vietnam’s relatively cosmopolitan orientation is simply a matter of size. While Vietnam’s ~100m population is by no means small by Southeast Asian standards, its population remains slightly over ⅓ the size of Indonesia and its GDP, the fourth smallest in ASEAN, is slightly smaller than that of Singapore. It is no wonder, then, that in meeting with Vietnam-based entrepreneurs, several wanted to discuss expansion into Indonesia, while after eight years, I can recall only once such conversation with an Indonesian startup interested in entering Vietnam.

The future: An argument for stability

In the ten years since I last visited HCMC and in the almost forty years since Đổi Mới, Vietnam’s economic growth has transformed the country and the lives of its citizens. The outlook for the next ten (or forty) years can perhaps be viewed through a framework of the growth Vietnam can achieve vs. the policies it chooses to pursue.

In terms of whether Vietnam can sustain its meteoric rise, the Vietnamese labor market has yet to show signs of the Chinese manufacturing labor crunch that previously pushed manufacturers South into Vietnam. Vietnamese manufacturing wages grew roughly 25% from 2016-2020, roughly in line with similar manufacturing-oriented markets, despite Vietnam’s rapid level of development and continued movement up the manufacturing value chain via increased assembly of higher-value goods. Adding to these tailwinds, continually increasing tensions between the U.S. and China have led many global companies to diversify their manufacturing base via parallel supply chains consisting of those allied with China and those allied with the U.S. As it has before, Vietnam’s position as a low-cost labor market geographically near to, but politically independent from China, will allow it to continue benefiting from a world increasingly split between the U.S. and China.

Whether Vietnam will choose to continue the policies similar to those that have contributed to its recent success largely comes down to its relationships with the world’s two great economic powers: the U.S. and its neighbor, China. Historically, Vietnam’s relationship with China has been complicated, owing in large part to China ruling Vietnam for nearly 1,000 years. More recently, political tensions between Vietnam and China have resurfaced, for example, in the 2014 China-Vietnam Oil Rig Crisis (aka “The Hai Yang Shi You 981 standoff”) in which China temporarily positioned an oil rig in a disputed area of the South China Sea, resulting in waves of ant-China protests across Vietnam.

Vietnam is currently undergoing a substantial political shakeup, ostensibly as part of a crackdown on corruption referred to by Vietnam Communist Party (VCP) General Secretary Nguyễn Phú Trọng as Vietnam’s “blazing furnace.” Badass nickname aside, this crackdown has resulted in the removal of an array of senior Vietnamese government officials, including two deputy prime ministers and the country’s prior president. In March, 20203, the country named Võ Văn Thưởng, a supposed Trọng loyalist, as its new President.

Key to Vietnam’s continued economic development are both the internal motivations behind current political shakeup and what effect, if any, this will have on country’s relations with both China and the United States. With regards to the motivations behind the current crackdown, some have painted the changes as a battle between “pro-Western” and “pro-Chinese” factions within the Vietnamese government, with the recent expulsions representing a purge of “pro-Western” elements. Given this line of thinking’s parallels to the “tigers and flies'' anti corruption drive that purged factions of the Chinese Communist Party and facilitated Xi Jinping’s monopoly of power, the implications for Vietnam’s continued economic development could be significant. Critically, others suggest that Vietnam’s anti corruption drive should instead be taken more or less at face value and does not represent a fundamental shift in Vietnam’s posture toward either the United States and China. Decades of Vietnamese policy stability, despite numerous leadership changes within the Vietnamese government, reinforce the Alfred E. Newman-esque “What, me worry?” theory of stability.

Unlikely to win in a military confrontation with China and with so much to lose economically by alienating the U.S., it’s easy to see why Vietnam may want to continue threading a needle between the world’s two great, and increasingly adversarial, economic powers. It is this choice that will determine whether HCMC’s tale of two cities will remain an apt analogy for the country’s continued ability to find a balance between West and East.

A sincere thanks to Alwin Low, Max Robinson, and most especially, Jeremy Au at Brave Southeast Asia for their feedback and for encouraging me to just start writing.

Another observation from my time in Vietnam, but not discussed above, is the Vietnamese economy’s reliance intertwined operating and financial companies. The late 2022 Van Thinh Phat Holdings scandal is but one example of how this approach can go terribly wrong. Please let me know in the comments if you’re interested to learn more about this, or any other topic. Thanks for reading!

Great post Matt! Hopefully catch you on another HCMC visit ...

Great read Matt. My Vietnam experience 70–73 was much different. Then living in San Diego for 50+ years with a large Vietnamese refugee population I watched that community go from rags to riches.

It seems that the Vietnamese culture flourished in both parts of the globe, while still hanging on to their culture. All the best, Ed